Among their many ‘must do’ tasks, STPs need to challenge health inequity.

In an address to delegates at the Health and Care Innovation Expo in September, National Director for Commissioning Operations and Information at NHS England, Matthew Swindells, identified three areas that Sustainability and Transformation Plans (STPs) needed to address and find answers to:

- Reduce health inequalities.

- Improve quality and access.

- Achieve 1 and 2 above within the financial envelope that has been set.

In short, NHS England is calling for a forensic analysis of the quality, equity and efficiency of the care currently being provided by the NHS.

Let us consider for the moment the first of these challenges, health inequalities. Few would disagree that there is an urgent need to address health inequalities. In truth there is nothing particularly new here.

In August 1980 the Department of Health and Social Security published the Report of the Working Group on Inequalities in Health. The Black Report (named after chairman Sir Douglas Black, President of the Royal College of Physicians) showed in detail the extent to which ill-health and death are unequally distributed among the population of the UK, and — rather alarmingly — suggested that these inequalities had been widening rather than diminishing since the establishment of the NHS in 1948.

It should be noted that when making this observation the Report concluded that these inequalities were not mainly attributable to failings in the NHS, but rather to the many other social inequalities influencing health: income, education, housing, diet, employment and conditions of work.

Interesting this because I strongly suspect that it is this fact that is leading many in Local Government to question how STPs alone (and remember they are essentially a NHS driven initiative) can fix the current problems facing the NHS. At least one council leader has recently described STPs as a “sort out the NHS first” approach.

2010 saw publication of the Marmot review[1] into health inequalities in England. The report spoke to the continuing social and economic cost of health inequalities and interestingly noted the vital role that local councils had to play in building the wider determinants of good health in supporting individuals, families and communities. Marmot stressed the requirement for action across the social determinants of health “and beyond the reach of the NHS”. I strongly suspect that this particular point has not been lost on local councils now part of the STP planning process.

While the debate around health inequalities has therefore been with us for decades, in the UK at least, less has been written on the subject of health inequity.

The late Barbara Starfield (Distinguished Professor, Department of Health Policy and Management, Johns Hopkins University) articulated the issue brilliantly in her 2011 article, The hidden inequity in health care.

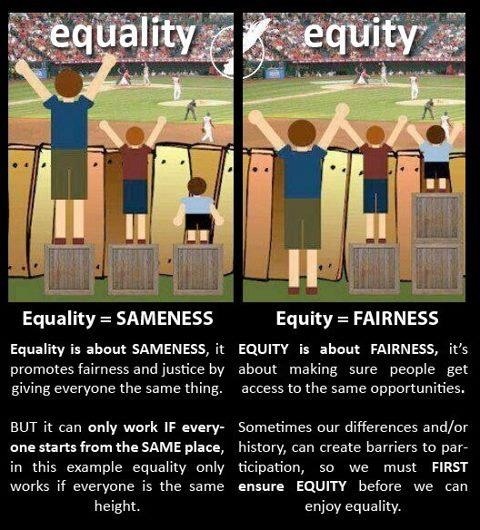

The distinction between inequity and inequality is nuanced but worthy of note.

Professor Starfield writes that inequality is a broad term “generally used in the human rights field to describe differences among individuals some of which are not remediable.”

Inequity, she states, is “the presence of systematic and potentially remediable differences among population groups defined socially, economically or geographically.”

The emphasis is mine.

Professor Starfield speaks of two types of inequity:

- Horizontal inequity, where people with the same needs do not have access to the same resources.

- Vertical inequity, where people with greater needs are not provided with greater resources.

Professor Starfield also observed that different population subgroups have different needs and some of those subgroups have greater needs than others.

As they embark on their population health journey, one of the key roles of the STPs will be to quantify and describe these different needs. Moreover, as the Starfield article points out, it is important that any population health analysis should focus not on single disease conditions, but on the burden of multi-morbidity observable in a local population.

This is important because it relates to one of the fundamental aspects of the Triple Aim, namely cost; or more specifically lower per capita cost for the taxpayer.

Let nobody be in any doubt that given the financial challenges faced by the NHS, a discussion of costs will dominate STP thinking and planning. We see this already in those plans already made public. The fear is that for a great many of the general public STPs will always be associated with cuts.

Even within certain NHS circles I have heard the Triple Aim re-defined as the money, the money and the money.

This brings us back to multi-morbidity because studies show that the greater costs of care are driven not by the existence of a chronic disease alone but by multi-morbidity. To quote Professor Starfield once more, “What makes certain people and populations costly is not that they have more chronic disease. It is that they have more types of morbidity.”

The case study below from Slough CCG demonstrates the point well.

An examination of multi-morbidity is of course a population health issue and population health management is very much in vogue at the moment. It occurs to me that population health programmes that have the best chance of success will be those that demonstrate an understanding of the importance of multi-morbidity and its impact on the local health and care economy. Studies show that not only is multi-morbidity common; it is in fact the norm.

Multi-morbidity (rather than single disease) approaches are borne of a whole person view of the individual. A whole patient orientated view allows for a much more detailed understanding of health needs and can therefore offer a more precise and relevant means of addressing issues of equity.

Which brings us to the issue of unwarranted variation.

Primary care clinicians have long understood that case-mix varies between GP Practices and across geographical areas. The trick has been to quantify this variation and to describe it; only then can the underlying causes driving variation be addressed.

In the UK at least, the tools and expertise to drive this kind of analytics have tended to reside within Commissioning Support Units (CSUs) or Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs) and sometimes both. In the STP world where place (geography) trumps organisation, such tools and analytical approaches will need to be extended beyond their current reach.

Luckily the methodologies and analytical tools required to get the job done do not need to be invented. They are already with us.

[1] ‘Fair Society Healthy Lives’ (The Marmot Review) February 2010

Enter your email address and we’ll send you a link to the Slough CCG case study.

Your privacy is important, therefore we will never pass on your details to anyone else.

Dear Ana

Many thanks for taking the time to comment. I would agree that we need to look beyond existing NHS data sets, but I would contend that they provide an essential starting point. Much can be achieved through the acquisition of primary care, secondary care, community care, mental health, prescribing and social care data. The additional data sets you reference will undoubtedly add value (I am no health economist) but we should start with the low hanging fruit. Outcomes measurement is vital, but from where I sit there doesn’t appear to be a nationally agreed set of metrics that could be readily incorporated for the purpose at hand. As for population profiling and costing, it occurs to me that work in this area is inextricably related to an understanding of inequity. We need a rich understanding of how healthcare resources are delivered and consumed….and by whom. Such analysis can aid an understanding of whether scarce resources are being deployed to those population groups in greatest need. As I say I am not a health economist by profession (I note you are) and I stand to be debated on this. If you would like to contact me at nigel@sollis.co.uk then perhaps we could arrange a meeting. Kind regards. Nigel

I read the article, and I read the report, exited thinking someone is finally using health equity analysis tools in the NHS (e.g. Erreygers Concentration Index). How you jump from the complex subject of health inequality/inequity to population profiling using costing and presumably NHS data set is a mystery to me.

To understand (and tackle) health inequalities across STP we need to go beyond the usual NHS data, and incorporate income, education, race and rank variables paired with objective outcome measures.

The article started well, but did not offer any real data solution to help STPs.